The first time I sat inside Tokyo’s sumo arena Ryogoku Kokugikan, the room went quiet in a way I didn’t expect. Salt hit the clay, a canopy like a shrine roof floated over the ring, and then two huge men crashed together so fast I almost missed it. That’s sumo. It’s sport, but it’s also ceremony you can feel in your chest.

I’m a foreign resident who’s worked in the Japan travel industry since 2019, and I recommend sumo tournaments to travelers because it solves a lot of problems at once. It’s weather-proof, runs on time, and you don’t need Japanese to follow it. Even cheap seats give you the full rhythm of the day. In this guide I’ll show you what you’re actually looking at, how the tournaments work, where and when to go, how to get tickets, which seats make sense for your body, and simple etiquette so you can relax. I’ll also share easy ways to get close to the sport outside the arena: morning practice, chanko meals, small museums, and a Ryogoku day plan that fits into a normal Tokyo trip.

If sumo is new to you, good. It’s built for first-timers. Let’s make it make sense before you step inside.

How to Watch Sumo in a Nutshell

If you’re short on time, here’s the article in a nutshell.

Tournaments run six times a year, each for 15 days. Three are in Tokyo and three rotate through Osaka, Nagoya, and Fukuoka. Plan for the top divisions from about 2 to 6 pm. One ticket covers the whole day with a single reentry before 5 pm, so a lunch break is easy.

Buy early through Ticket Oosumo by PIA with English support, or a reseller like Klook or buysumotickets.com for convenience. Weekdays are easier. If sold out, try early morning same-day sales at the arena with cash, or look for retirement ceremonies.

Choose seats that fit your body. Chair seats are the best value and most comfortable. Box seats feel traditional but mean floor sitting. Ringside is rare and strict.

Ryogoku Kokugikan in Tokyo is the easiest arena day: steps from JR Ryogoku Station, clear sightlines, morning photo time, and chanko nabe inside. Keep quiet during the stare-down, move between bouts, and skip flash.

For extras, watch morning practice in a sumo stable, eat chanko at Yokozuna Tonkatsu Dosukoi Tanaka, and pop into the Sumo Museum or Eko-in Temple. Stay in Ryogoku if you can; The Gate Hotel Ryogoku by Hulic is excellent and convenient.

Understanding Sumo: Tradition and Culture

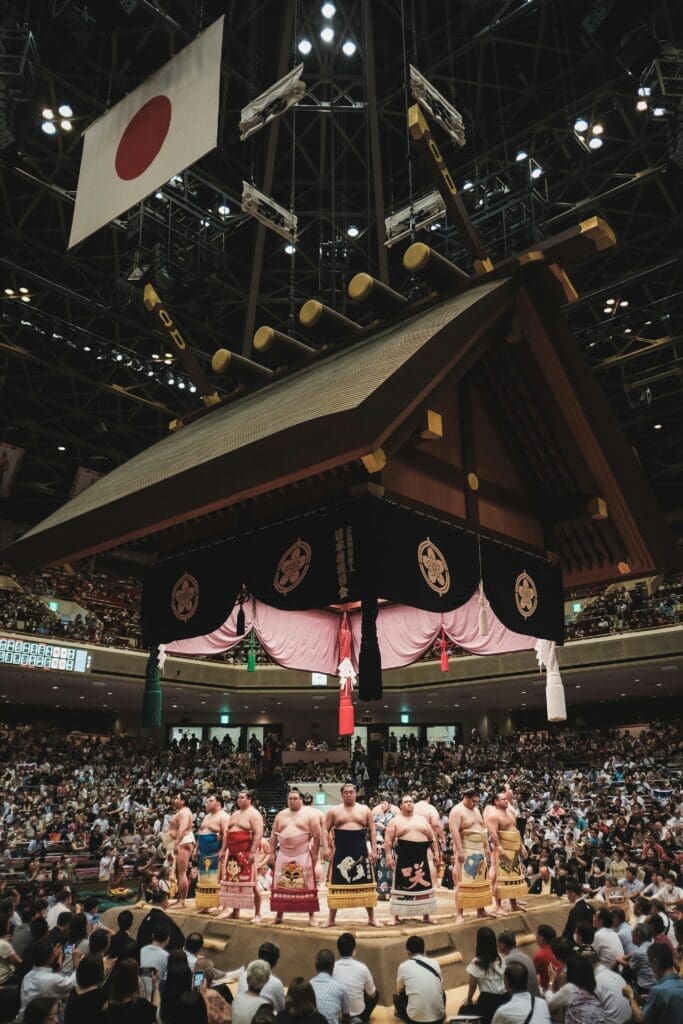

Sumo is Japan’s national sport, but it is also a living ritual. The first time I walked into Ryogoku Kokugikan, what hit me wasn’t just the size of the wrestlers. It was the feel of a shrine indoors. There is a roof hanging over the ring shaped like a Shinto shrine, white paper streamers above, and a ring that is purified again and again with salt. Once you notice that, the whole day makes more sense.

At its core, sumo is simple: win by forcing your opponent out of the ring or making them touch the ground with anything but their feet. Bouts usually last seconds. The long build-up, the chants, and the careful movements are the heart. That rhythm is what makes sumo different from any other sport you will watch in Japan.

History and Sumo Nowadays

- Origins: Sumo’s roots go back more than a thousand years. Court wrestling in the Heian Period was known as sumai no sechi, performed for the emperor and for the gods. You still see echoes of that courtly style in the clothes of the referees and the formal ceremonies.

- Shinto connection: The ring, or dohyo, is treated as sacred space. Before a tournament starts, officials hold a small ceremony to consecrate the ring, and offerings are placed beneath the surface. When people say sumo is full of ritual, this is what they mean. It grew from rites tied to harvest, purity, and community, not just entertainment.

- National status: Professional sumo is contested only by men, and it is run under a very structured system of stables and ranks. Wrestlers come from all over the world now, but when a top division star does well, you feel the whole country pay attention. Sumo sits in that rare space where sport and tradition carry equal weight.

Rituals and Customs

Knowing what you are watching turns the pre-bout “waiting” into the best part of the day.

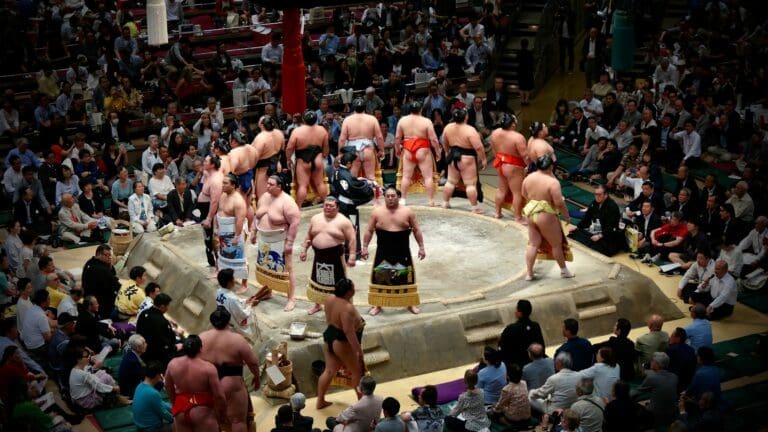

The ring and the people around it: The dohyo is a clay platform with a circle made from rice-straw bales. Above, a canopy mimics a shrine roof. Around the ring sit judges in formal black kimono. If a call is close, they step in for a discussion, and you may get a rematch. The referee, or gyoji, wears a brightly colored kimono and holds a war fan to signal his decision. The ushers who sing the names and maintain the ring are called yobidashi; they rake the sand and rebuild the ring edge constantly. I like watching them work between bouts. It is quiet and precise.

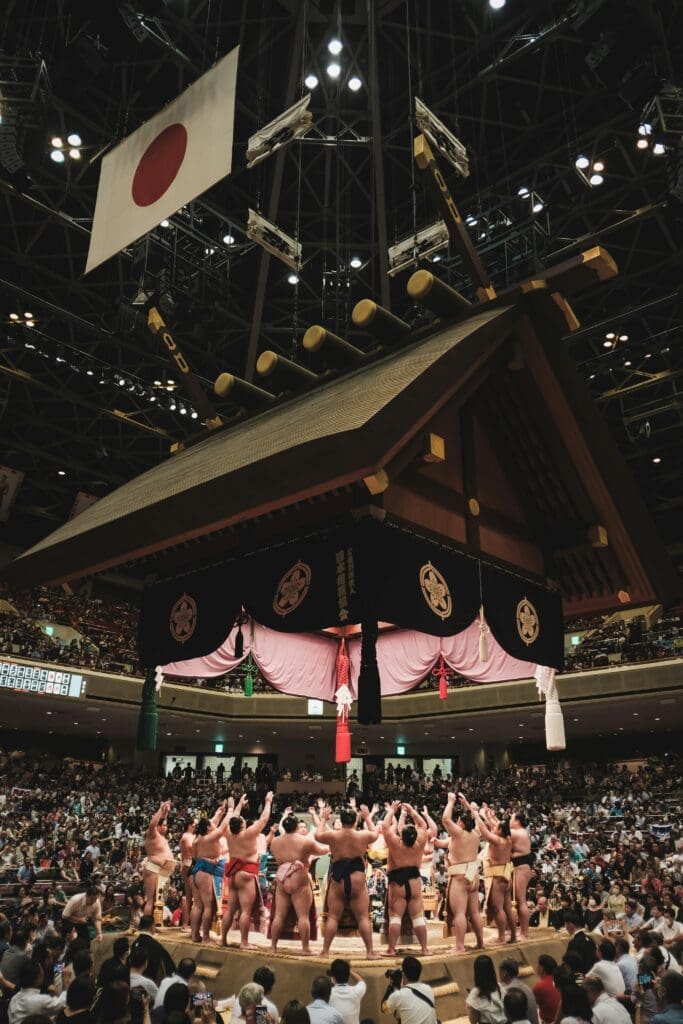

Ring-entering ceremonies: Before the afternoon’s top divisions, wrestlers file in for the dohyo-iri, or ring entering ceremony. They form a circle, clap, and raise their hands to show they carry no weapons. When a yokozuna appears, he wears a thick white rope around his waist like the sacred rope at a shrine, with two attendants at his side. This is one of those moments where the whole arena hushes.

Pre-bout sequence: Wrestlers step into the ring, squat, lock eyes, then step out again. They stomp their legs high (shiko) to drive away bad spirits, toss salt to purify the ring, rinse their mouths with “power water,” and wipe with paper. They may repeat this up to three times. The building tension is the point. When they finally launch into the tachiai (the initial charge), the collision is shocking even after you have seen a dozen bouts.

The bout and the winner’s gesture: The match ends when any part of the body other than the soles touches the clay or when someone steps out. Afterward, the winner often performs a brief ritualized arm sweep called chiri-chozu, palms open to show no weapons. It is a nod to older rules of honor that still thread through the sport.

End-of-day bow ceremony: The last thing you will see is the bow-twirling ceremony, yumitori-shiki, performed by a lower-ranked wrestler. It is brief, formal, and a satisfying bookend to the day.

Dress and appearance: Wrestlers wear a thick silk belt called a mawashi. In the top division their hair is styled into a ginkgo-leaf topknot, which adds to the old-world feel. Officials and attendants are just as formal. It is one of the few modern sports where the clothing tells you the hierarchy at a glance.

Etiquette in the arena: Applause is welcome, but big shouts usually come at the decisive moments. People take the ceremonies seriously. The ring is treated like a shrine area, so you will not see anyone entering it outside of the people involved in the sport. I suggest arriving a bit early to watch the ring-entering ceremonies and the way the sand is smoothed before the top bouts. That is where you feel the tradition most clearly.

If this sounds ceremonial, it is. But it is not stiff. Sumo is a loud, living thing. Once you settle into the rhythm of ritual, clash, and release, you start to see why Japan still treats it as more than a game.

Sumo Tournaments: When and Where to Go

Grand Sumo runs on a simple calendar that makes planning easy. There are six main tournaments each year, each one lasting 15 straight days. Three happen in Tokyo and the other three rotate through Osaka, Nagoya, and Fukuoka. Matches run all day, but the atmosphere builds toward the late afternoon when the top divisions take the ring. If you only have a couple of hours, aim for mid‑afternoon to 6 pm. The final bout usually ends right on 6, so it is not an evening sport.

All tournament tickets are valid for the full day, and you can leave the arena once and reenter later the same day. I often arrive early for a look around, step out for lunch, then come back for the headliners.

Major Tournaments and Locations

- January — Tokyo (Ryogoku Kokugikan)

- March — Osaka (EDION Arena Osaka)

- May — Tokyo (Ryogoku Kokugikan)

- July — Nagoya (Dolphins Arena, also called Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium)

- September — Tokyo (Ryogoku Kokugikan)

- November — Fukuoka (Fukuoka Kokusai Center)

For 2026 in Tokyo specifically, the scheduled tournament dates are:

- January 11–25

- May 10–24

- September 13–27

Here is the full 2026 schedule:

| Tournament | Venue | Advanced Tickets are sold from | Sumo Ranking is announced on | First Day . Final Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The January Tournament | Kokugikan (Tokyo) | December 6, 2025 | December 22, 2025 | January 11, 2026 . January 25, 2026 |

| The March Tournament | EDION Arena Osaka (Osaka Prefectural Gymnasium) | February 7, 2026 | February 24, 2026 | March 8, 2026 . March 22, 2026 |

| The May Tournament | Kokugikan (Tokyo) | April 4, 2026 | April 27, 2026 | May 10, 2026 . May 24, 2026 |

| The July Tournament | IG Arena (Nagoya) | May 16, 2026 | June 29, 2026 | July 12, 2026 . July 26, 2026 |

| The September Tournament | Kokugikan (Tokyo) | August 8, 2026 | August 31, 2026 | September 13, 2026 . September 27, 2026 |

| The November Tournament | Fukuoka Kokusai Center | September 19, 2026 | October 26, 2026 | November 8, 2026 . November 22, 2026 |

You can easily find the tournament schedule as far as two years ahead on the official website of the Japan Sumo Association.

Each basho (tournament) runs 15 days, including weekends, and every rank competes daily. If your trip doesn’t line up with a basho, keep an eye out for special events like retirement ceremonies. They often happen at the same venues, include exhibition bouts and demonstrations, and can be a fun way to get a taste of sumo outside the main calendar.

The Sumo Arena Experience

Ryogoku Kokugikan in Tokyo is the heart of pro sumo. It is a purpose-built arena with great sightlines, a small Sumo Museum on the first floor, tons of souvenir stands, and easy food options inside. Access is painless: it is 1–2 minutes from JR Ryogoku Station’s west exit on the Chuo–Sobu Line, or about 5 minutes from Toei Oedo Line’s Ryogoku Station. From Shinjuku, Shibuya, Yoyogi, or Akihabara, the JR Chuo–Sobu Line takes you straight there.

Seating is split into three main types:

- Ringside seats: closest to the dohyo. They are limited, pricey, and typically set aside for patrons and serious fans. Wrestlers can and do land here, so these seats come with rules and age limits.

- Arena seats: standard chair seats, usually on the second floor, sold individually. Easiest option if you prefer a chair and a simpler purchase.

A typical day starts with the lowest ranks around 8:30 am, builds steadily from lunch, then the juryo and makuuchi divisions (and the yokozuna if one is competing) take over roughly 2:00–6:00 pm. If you only want the biggest names, I suggest arriving around 2:30–3:00 pm. If you want photos of the ring and the salt toss without crowds blocking your view, go in the morning, take a break outside, and return later. The single reentry rule makes that easy.

Food and facilities are straightforward. Concessions sell bento, snacks, beer, and often chanko nabe, the hearty hot pot associated with wrestlers. Restrooms are plentiful and clean, and there is space to browse souvenirs between matches. In summer tournaments, arenas can feel warm, so I recommend light clothing and a small towel.

Outside Ryogoku Kokugikan you will find sumo-themed statues, lots of chanko restaurants, and a few museums nearby. It is one of those neighborhoods where I actually like to arrive early and linger, even if my seat is not the closest to the ring.

How to Get Tickets and Plan Your Visit

Sumo is popular and tournaments sell out fast, but you still have options. The short version: buy through the official site as soon as sales open, consider weekday dates, and if you miss out, try early-morning same-day tickets at the arena or look for special events like retirement ceremonies. Your ticket lets you stay all day, and you can leave once and reenter before 5:00 p.m., which makes planning around lunch easy.

Ticket Types and How to Buy Them

You’ll see three main categories of seats:

- Ringside seats: closest to the ring, very limited and priced accordingly. Usually snapped up by long-time fans and invited guests.

- Box seats (masu): small tatami-style boxes for 2–4 people. Great atmosphere, but you’ll sit on the floor.

- Arena/chair seats: standard seats, typically on the second level. Easiest on the knees and wallet.

Where to buy:

- Official sales: Ticket Oosumo by PIA is the official partner and has English support. Sales usually open roughly one month before each tournament. I recommend booking the day sales start, especially for weekends and holidays. After purchase, you will need to go get your tickets at Seven Eleven once in Japan.

- Agencies/resellers: there are reputable services that buy on your behalf. They’re usually much easier to use than the official website and can ship to your hotel, but convenience comes with a markup. I recommend Klook or buysumotickets.com, but there are several other resellers as well. If a site asks for a local phone number or tricky registration, an agency can be a helpful workaround.

- Same-day tickets at the arena: not guaranteed, but when available they’re sold first-come, first-served. Get to the main entrance early (think around 6–7 a.m.) with cash. If you score a ticket, go nap or explore, then come back for the top divisions in the afternoon.

Useful details:

- All tickets are valid for the whole day. You can leave the building once and reenter before 5:00 p.m.

- If tournaments are sold out during your dates, check for special events like retirement ceremonies (danpatsu-shiki) at Ryogoku Kokugikan. They often run late morning to late afternoon, include demonstrations and exhibition bouts, and are typically cheaper than tournament days.

- Prices vary by city, day, and seat type. As a rough guide, upper arena seats can start around ¥3,500, while what’s left on the day-of often lands in the ¥5,000–11,000 range. Box seats start from about ¥34,000 per box.

I suggest setting a calendar alert for the on-sale date, aiming for weekdays if possible, and having a backup plan to try the box office early in the morning if you miss online sales.

Choosing Your Seat

Each seat type changes the feel of your day.

- Ringside

Closest you can get. The impact is incredible, but availability is tiny and prices are high. It’s not the practical choice for a first visit unless you get very lucky. - Box (masu)

You’ll sit on cushions with shoes off in a compact tatami-style box for 2–4 people. It’s intimate and feels very “sumo,” but be honest about your flexibility. If your knees aren’t happy on the floor, you won’t enjoy four hours here. Boxes usually make sense for couples or small groups splitting the cost. If you do book a box, wear socks you’re happy to show and consider a small foldable cushion. - Arena/chair

Individual seats with back support, usually on the second level. This is the best value for most travelers. The view is further, but you get comfort, easy access to food, and clear sightlines. If you’re tall, traveling with kids, or planning to stay through the top divisions, I recommend chair seats.

My rule of thumb: chair seats for comfort and price, box seats for atmosphere with a flexible group, ringside only if it falls into your lap. If you care about photos, aim for lower rows or arrive in the morning to shoot before ringside fills up.

Before you buy, it helps to look at photos of the arena map so you know what the view and legroom are like in each section.

Before You Go: Tips for Visitors

- Timing and day plan

Bouts start early (around 8:30 a.m.) with lower ranks. The big names compete roughly 2:00–6:00 p.m. A simple strategy that works well: pop in during the quiet morning for photos, take a lunch break outside, then return for the top divisions and the closing ceremonies. Remember you get one reentry before 5:00 p.m. - Heat and comfort

Arenas can run warm, especially in summer. Wear breathable clothing. If you booked a box, a small sit pad helps a lot. Chair seats are kinder for long sessions. - Cash and purchases

Bring cash for same-day ticket attempts and small purchases. Even in big venues, not every counter is card-friendly. - Bags and logistics

Avoid large luggage. Use station coin lockers before you go in, then you can move around easily and enjoy the concourse. - Footwear and dress

No formal dress code. For box seats you must remove shoes, so plan socks accordingly. If you’re not comfortable sitting on the floor, pick chair seats. - Accessibility

Box seats require floor seating and stepping over a low edge, which can be tough. Chair seats are the safer bet if mobility is a concern. Major arenas have staff to assist and typically offer designated accessible seating; contact the venue if you need arrangements. - Photos

The best time for unobstructed ring shots is the morning before the front rows fill. Later on, just shoot from your seat and enjoy the show.

If you only remember three things: book as early as you can through the official site, choose a seat type that matches your body not your ego, and plan your day around that 2:00–6:00 p.m. window when the top divisions collide.

What to Expect on Sumo Day

Your ticket covers the whole day, and the day is long. Bouts begin early with the junior ranks, then build to the top divisions in the late afternoon. The final match usually wraps up by 6 pm. If you want the full arc, arrive in the morning, wander the arena while it’s quiet, and settle in later for the big names. If you only have a couple of hours, aim for roughly 3 to 6 pm.

I always suggest starting early for photos and to watch wrestlers warm up when the seats are still empty, grab lunch nearby, then come back for the headliners. You get the calm, the rituals, and the roar. There is usually a single reentry allowed before 5 pm, so stepping out is easy.

Outside the arena you’ll see colorful banners, and you’ll hear the big drum in the morning and again when the day ends. Top-division wrestlers tend to arrive mid-afternoon. If you stand near the main entrance you might catch them walking in, which is a fun bonus before the main show.

Match Schedule and Flow

- 8:30 am to around noon: Lower divisions

The hall is quiet and half empty. Great time to explore, take photos near the ring from public aisles, and learn the rhythm. The rules are simple. Win by pushing your opponent out of the ring or making any part of him other than the soles of his feet touch the ground. - Around 2:00 pm to 3:30 pm: Juryo division

The second-highest division brings more ceremony and a bigger crowd. You will see the first ring-entering ceremony where the group of wrestlers steps onto the dohyo together in ornate aprons, then bows and leaves.

Every bout is short. Many end in seconds. The slow part is the build-up. Wrestlers crouch, glare, step away, throw salt to purify the ring, and repeat. At the top level they can repeat this up to a few times. Do not get impatient. That tension is part of the show.

One ticket is good for the entire day. You can leave once and come back before 5 pm, which is perfect for a late lunch. I suggest arriving before lunch if you want the best photos and then returning for Juryo through the final match. If you are bringing kids, coming for just the late afternoon is usually the sweet spot.

Watching the Action: Etiquette and Enjoyment

- During the stare-down, keep it quiet. After the throw of salt and clap, the hall settles. When the impact comes, you can cheer. Clapping and calling out a wrestler’s name is normal, booing is not.

- Do not stand up or walk the aisles mid-bout. Move between matches. Each bout is quick, so you never wait long.

- Photography is fine from your seat. Avoid flash, and skip tripods or big rigs that block views. For close shots, go early in the morning when the front rows are still empty and staff are relaxed about people taking pictures from public aisles. Later in the day, stick to your seat.

- In box seats, shoes off. Sit cross-legged or side-saddle within your square. Keep bags and feet inside your area so staff and neighbors can pass.

- Never touch the ring or step onto the platform, and resist the urge to throw seat cushions even if a huge upset happens. It used to be a thing. It is not allowed now.

- If you do not understand Japanese, you will still follow it. The gyoji (referee) calls the start, the scoreboard above the ring shows the wrestlers, and the outcome is obvious. I like to pick one side in each match and watch only his feet and belt grip. It makes even the short bouts more tactical.

- If you want autographs or photos with wrestlers, try outside the building after the final match. Inside, security keeps things moving.

I recommend taking a break mid-afternoon to reset your ears and come back fresh for the ring-entering ceremonies, which are visually the best part if it is your first time. If you want to catch the yokozuna entrance, be seated a little before 4 pm.

Food, Drink, and Facilities

Sumo days are easy to enjoy without leaving your seat. You can eat and drink inside, and the food is part of the fun.

- Food and drink

Expect bentos with wrestler portraits, hot yakitori, and cups of chanko nabe, the hearty stew wrestlers eat at home. There is beer, sake, soft drinks, and plenty of snacks. Lines are short in the morning and spike just before the top divisions. If I plan to stay through 6 pm, I either eat an early lunch outside or buy food by 2 pm and avoid the rush. - Restrooms and breaks

Restrooms are frequent but get lines around big ceremonies and right after the final match. Go during lower-division bouts or a few minutes after the ring-entering ends to skip the queues. There are vending machines and concession stands throughout the concourse, plus water at some counters. - Souvenirs

Shops inside sell towels, cushions, sweets, and stable-branded goods. If you want a specific bento or a popular towel, buy earlier in the day. Some items sell out before the main bouts. - Comfort and small things

Arenas can run warm once the crowds arrive, even in winter. Wear breathable layers. I always bring a hand towel and a small portable fan in summer. Arena seats are regular chairs; box seats are on the floor. If you struggle to sit on the floor for long, stick with chair seats. Keep your bag small so it fits under the seat. - Reentry and cash

Plan your one reentry before 5 pm if you are stepping out. Many concession stands accept cards now, but I still bring cash for speed and the odd cash-only counter.

That is the day in a nutshell. Arrive early if you love photos and ritual, come late if you want star power and noise, or do both with a lunch break in between. I prefer the full arc because sumo makes the most sense when you see the slow climb from the unknown teenagers in the morning to the yokozuna bowing under the lights at 6 pm.

Beyond the Arena: Sumo Experiences in Japan

If tournament tickets are sold out, or you just want more, there are plenty of ways to get close to sumo without sitting in a seat at the Kokugikan. I recommend mixing one or two of these into your Tokyo days, especially if you are staying around Ryogoku.

Sumo Stable Visits and Morning Practice

Watching morning training, called keiko, is the most intimate way to see what makes rikishi who they are. Practice usually runs in the early morning, and the room is quiet. The air is heavy, you hear every stomp and slap of bodies. It is intense and very human.

How to go

- Some stables accept visitors directly. A few post practice times, others require advance permission in Japanese. If that sounds stressful, I recommend booking a guided visit. This is much easier and my preferred method as well. Tours usually handle the communication, timing, and etiquette briefing, and many include a Q&A or chanko lunch afterward.

- I recommend booking through Wabunka. A private guide will accompany you so that you can ask all the questions you want. If you’re not an early bird, Wabunka also offers an afternoon practice viewing that also include a tour of the nearby sumo facilities.

- If a private guide is too expensive for you, I recommend booking a group tour. Many platforms offer those, but I recommend Viator, Klook, or GetYourGuide. The tour will be less intimate and personalized, but you will see the morning practice all the same.

- A rare easy option in Tokyo is Arashio-beya in Nihonbashi. When they allow it, you can watch from the street-side windows for free with no reservation. Schedules change, so check their latest practice days before you go. Fun fact, I actually used to live a few streets away from Arashio-beya. The window is around 5 meters long but 1 meter high. There were usually 20-30 people trying to peek inside. I imagine even more now, so that might not be the most comfortable option.

What to expect

- Practice starts early, often around 7 to 8:30 a.m., and can run a couple of hours. Junior wrestlers go first, seniors at the end.

- Most stables close to visitors during tournaments or when traveling to Osaka, Nagoya, or Fukuoka. Off-days happen. Be flexible.

Etiquette that really matters

- Arrive a few minutes early, turn your phone to silent, and speak only if staff speaks to you.

- No flash, no video unless clearly allowed, and never step on the dohyo.

- Sit still and avoid blocking doorways or sightlines. Shoes off if you enter the stable. I bring socks and a small towel or foldable cushion because floors are hard.

- Dress modestly and skip strong perfume. Heels are a bad idea on tatami.

- Follow the stablemaster’s instructions immediately. If they ask you to move, just move.

If you cannot get inside, it is still worth visiting the Kokugikan in the afternoon to see wrestlers arrive under the colorful banners. You will hear the taiko drum in the morning and evening that marks the start and end of the day. I have stood outside with a coffee just to watch the steady flow of topknots and robes. It never gets old.

One more idea: retirement ceremonies

- Danpatsu-shiki, the topknot-cutting events, are often held at the Kokugikan and are open to the public with paid tickets. They include demonstrations, comic sumo, and tributes, and usually cost less than a grand tournament seat. If you see one during your dates, grab it. It is celebratory and surprisingly moving.

Sumo-Themed Restaurants and Dining

Chanko nabe is the stew that powers wrestlers through those 10,000-calorie days. It is hearty, protein-heavy, and best shared. Ryogoku is full of chanko restaurants, including places run by former wrestlers with memorabilia on the walls.

Good picks I suggest

- Yokozuna Tonkatsu Dosukoi Tanaka (east Tokyo): run by a retired wrestler. They have a small ring, demonstrations on certain days, history talks, and even let guests step into the ring to fight with the sumo wrestlers and for photos. Lunch features tonkatsu and chanko, with some evening events too. It is playful and welcoming even if you know nothing about sumo. Book on Viator.

- Asakusa Sumo Club: several short shows daily with sofa seating, simple meals like fried chicken, inarizushi, and chanko, plus audience participation. You can try a mawashi challenge or suit up in a silly inflatable for a safe bout. It is touristy, but if you want an easy, hands-on taste of the sport, it delivers. Book on Viator or Klook.

Practical chanko tips

- Portions are big. Bring friends or ask about half-size or lunch sets if you are solo. I usually book dinner in Ryogoku on a non-tournament day so staff have more time to chat.

- Vegetarian or vegan? Ask when you book. Many guided experiences can arrange plant-based broths and vegetables if you give notice.

- Some restaurants show live NHK coverage during tournaments. If watching the day’s bouts is your priority, confirm when you reserve.

Sumo Museums and Landmarks

You can spend a great half-day in Ryogoku connecting the dots between the sport and the neighborhood.

- Sumo Museum (Kokugikan, first floor): small, focused exhibits that rotate through kesho-mawashi, woodblock prints, and champion histories. It is often free, but opening hours change during tournaments and some days it is only open to ticket holders. I pop in whenever I am at the arena because 20 minutes here adds so much context.

- Eko-in Temple: the spiritual home of early Edo-period tournaments. It is a quiet stop that ties the sport back to its roots in memorial and community events.

- Nearby museums: the Edo–Tokyo Museum is closed for renovations until 2025, but the Sumida Hokusai Museum and the Japanese Sword Museum are open and close enough to combine with a Ryogoku walk.

Outside Tokyo during tournament months, look for temporary exhibits near venues in Osaka, Nagoya, and Fukuoka. They often put up banners and small displays, and local chanko restaurants get lively with visiting fans and stables.

If you plan your trip around sumo, I recommend spending at least one night in Ryogoku (see Where to Stay for Sumo Events further below for hotel recommendations). Walk in the morning, stable visit if possible, chanko for lunch, museum in the afternoon, then watch arrivals or a special event. Even without a tournament ticket, you will come away feeling like you actually met the sport rather than just read about it.

Helpful Advice for Sumo Fans

This is the stuff I wish someone told me before my first basho. Nothing fancy, just the practical things that make your day smoother and more fun.

What to Wear and Bring

- Wear breathable layers. Arenas can feel warm in the afternoon when the crowd builds, but winter tournaments start out chilly. A light jacket you can stash under your seat works best.

- Socks you don’t mind showing. In box seats (masu), you take your shoes off and sit on the floor. I suggest slip-on shoes for quick on/off.

- If you have sensitive knees or back, bring a thin travel cushion for box seats. The boxes come with small cushions, but a little extra padding helps if you’re there for hours.

- Cash. If you’re trying for any on-the-day tickets at the arena, it’s cash only. Some food and souvenir stalls take cards now, but not all. I always keep a few notes for speed and convenience.

- A refillable bottle and light snacks. Concessions sell everything from snacks to chanko nabe, but lines get long between 2 and 4 p.m. I like eating early, then topping up later if needed.

- Your ticket strategy. Tickets are valid all day, with one reentry allowed before 5 p.m. Keep your stub safe and plan your meals around that window. A common rhythm is morning photos, lunch break, then back for the big guns in the afternoon.

- Camera rules in mind. Photos are fine from your seat, but skip the flash and don’t block aisles. If you want closer shots, arrive early; in the quiet morning hours ushers are usually fine with you stepping closer for a minute between bouts. Be quick and polite.

- If you’re gambling on day-of seats, arrive early. I suggest lining up around 6 a.m. with cash. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s the only way when popular days sell out. Once you’ve bought your ticket, go nap and come back for the top divisions later.

- Sun and queue comfort. Morning lines are outdoors. A hat, light sunscreen, and a small umbrella help if the weather turns.

Quick seat comfort reminder:

- Chair (arena) seats are standard chairs sold individually and the most comfortable for most visitors.

- Box (masu) seats fit 2–4 people, sold by the box, shoes off, and you sit on the floor. Good with friends, less fun if your knees protest.

- Ringside is special and limited. Expect strict rules and no wandering.

Accessibility and Language Support

- Choose chair seats if you have mobility, knee, or back concerns. Masu boxes look charming, but floor seating gets tough fast. I recommend chair seats for anyone who isn’t used to sitting on the floor for long stretches.

- Major sumo arenas have elevators, accessible restrooms, and designated wheelchair seating. If you need those, arrange in advance. When buying online, look for accessibility notes, or reach out to the ticket support desk before sales open.

- Buying tickets in English is easiest through the official Ticket Oosumo by PIA site. If you try the Japanese-only portals, expect phone number verification hurdles. I recommend sticking to the English site to avoid that.

- Language inside the arena is mostly Japanese, but it’s easy to follow once you know the flow. I suggest bookmarking the daily bout list (torikumi) in English on your phone and taking a screenshot before you go. It helps you track who’s up next without relying on the signage.

- If you want explanations while you watch, bring earphones and stream a live broadcast on your phone with data. Even if the commentary is in Japanese, seeing names and match order on screen helps a lot. The bouts are short; the visuals tell most of the story.

- Staff are helpful. Show your ticket and they’ll point you the right way. Seat numbers use western numerals, and ushers will guide you if you look unsure.

- If tickets sell out for your dates, look for special events like retirement ceremonies (danpatsu-shiki) at the Tokyo arena. They’re not every week, but when they happen they’re often easier to book and include demonstrations and lighthearted bouts. It’s a different vibe and generally cheaper than a sold-out tournament day.

Where to Stay for Sumo Events

If you’re watching in Tokyo, stay in or near Ryogoku. It makes everything easier.

Why Ryogoku works:

- The arena is 1–2 minutes from JR Ryogoku Station (Chuo–Sobu Line, west exit) and about 5 minutes from Toei Oedo Line’s Ryogoku Station.

- You’re surrounded by sumo life: chanko nabe restaurants, statues of famous rikishi, and the Sumo Museum inside the arena.

- Extra sights nearby include the Sumida Hokusai Museum and the Japanese Sword Museum. The Edo–Tokyo Museum is closed for renovations until 2025.

- It’s often cheaper than hubs like Shibuya or Shinjuku, and you won’t lose time commuting.

Hotels I recommend for convenience:

- Pearl Hotel Ryogoku: simple, close, and good value for location.

- Ryogoku View Hotel: a short walk to the arena with easy station access.

- The Gate Hotel Ryogoku by Hulic: higher-end, riverside views, still steps from the action.

For other cities:

- Osaka’s tournament is at Edion Arena Osaka. I suggest staying in Namba or Shinsaibashi for a quick walk and great food after the bouts.

- Nagoya’s is at Dolphins Arena (Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium). Sakae or Fushimi are practical bases with plenty to eat and do.

- Fukuoka’s is at Fukuoka Kokusai Center. Hakata or Tenjin keep you close with simple transport.

One last tip: if you care more about experience than proximity, book where you’ll enjoy your nights too. For me, staying in Ryogoku during a Tokyo tournament adds to the mood. I can grab chanko for dinner, stroll past the banners, and be in my seat without stressing about trains. That little bit of ease goes a long way on sumo day.

The Bottom Line

Treat sumo as your low-effort high-reward day. It runs on time, ends by dinner, and most of it you enjoy from your seat, which means less logistics and more observing. Make comfort your priority when you pick seats, then let the rituals do the heavy lifting. If you miss tournament tickets, a stable visit, a retirement ceremony, or just an afternoon in Ryogoku with chanko still gets you most of the feeling you came for. Going solo is totally normal. Everyone is watching the ring, not you. Build one day around sumo and you get a clear window into Japan without sprinting across the city. That calm in the pauses between bouts might be what you remember most.

Comments are closed.